Minesing Swamp - A Cautionary Tale

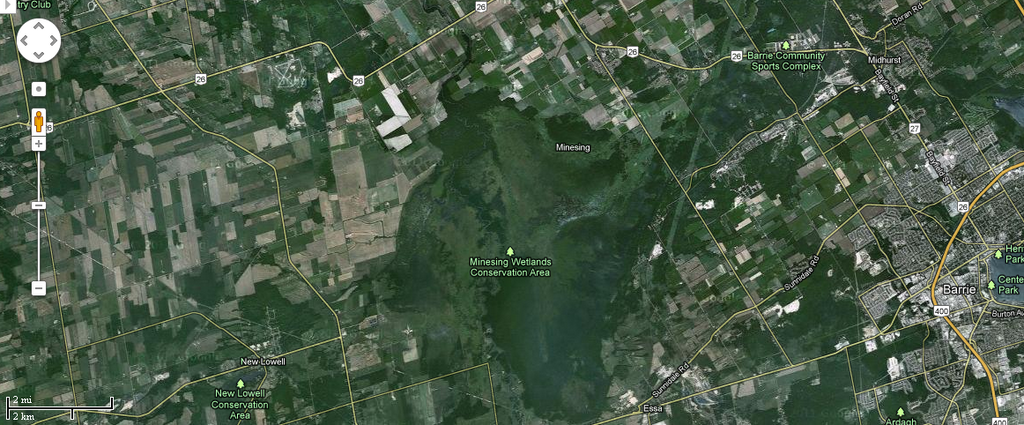

The Minesing Wetlands Conservation Area is roughly oval-shaped, about 6 miles on the N-S axis, about 4 miles E-W. The swamp itself is somewhat larger.

We decided to traverse the swamp, starting from Minesing Swamp – Willow Creek and ending up at Minesing Swamp - Edenvale .

That means we were basically travelling a letter "L", heading south-west, then turning North to meet up with the Nottawasaga River.

"A doddle", we said. Downstream all the way, we only need paddle enough to be able to steer. A lazy way to start the season.

It nearly killed us, I mean that literally.

We picked nice weather, but didn't realise what a wind would do to us. Friday's newspaper forecast said "Winds NNW 12-25 Km/h", but they were more like 60 Km/h, and a steady blow, not gusts.

Read on, dear reader, read on.

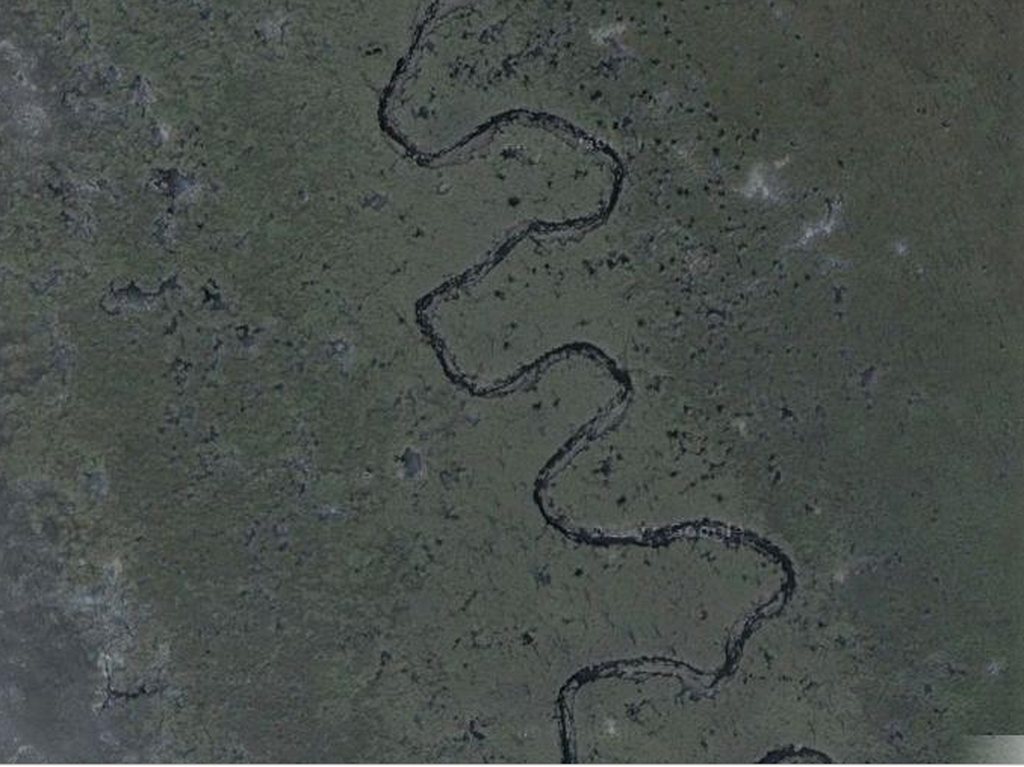

For the northward leg (of the letter "L" that the channel makes through the swamp), most of the legs run roughly east-west, and of course the wind is coming from the North. That meant that we had, say, three minutes paddling into a 60 Km/h wind, and then about ten minutes struggling to keep ourselves mid-channel on the east-west legs.

In short, our day became almost five hours of non-stop paddling in a very heavy wind.

It took us three hours strong paddling to reach the first bit of land where we could beach the canoe and stretch our legs, and at that point my body began trembling uncontrollably; I believe I was in the early stage of hypothermia.

For those first three hours we paddled non-stop, realising that while the map makes it look like a creek between two banks, the swamp is really a lake, about six kilometres diameter, with reed beds. The reeds are anchored four feet down in the lake bed, and where the reed leaves meet the surface lies a matted bed of dead leaves.

Bottom line: you can't swim to the shore, because you can't swim through the reeds; you can't walk to shore, because the reed bed won't support your weight. If the canoe capsizes, the only way out is to swim the channel to its mouth, and given the cold wind and the cold water, we'd die before we reached land.

On top of that, if the canoe capsized, there's no creek-bank to which we can scramble, and the canoe would probably drift away out of reach. Worse, it make take any fork in the downstream channels, so we'd not know where to follow.

There are no trees in the swamp, so we can't climb a treet and wait for a helicopter.

In short we were scared.

What did we learn from all this?

Lesson 1: Don't do a swamp alone; always do it with at least two canoes.

Lesson 2: Be very sure you know the swamp; canoeing a reedy-lake is like canoeing across the lake four or five times, owing to the extra distance brought by the meanders.

Lesson 3: Don't attempt a swamp (or a lake) if the wind is at all strong; while the breeze might die down, it might also pick up.

I have been asked "But you had life-vests, didn't you?". The answer is yes, but life-vest or not, the water is going to suck the heat out of your body; then you die.

I walked to the end of McNabb to check out the spot for launching, and was joined by a young pup; two fellows were putting in to head up the Nottawasaga to the blockage, portage over that, then head on to the Mad River; we met up with them at the blockage on our way downstream.

"Smile for the camera" I called out.

Here is the ditch that drains along McNab; the two fellows launched their canoe in the ditch at this spot and poled into the river.

Here is the track running North to McNab proper, and then to make a T-junction with Highway 26.

Fred collected me and we launched into Willow Creek at about 10:15. The air is calm, the sun warm, we are heading for an idyllic day, right?

Here's a look back at Fred's car parked in the lot on George Johnston Road.

"A shrine to a dead canoeist" jokes Fred. These markers help guide us through the swamp; in this case the right-hand arm comes to a point, and is painted red.

We see quite a few of these as we paddle along.

The current in this canal-like stretch is quite strong.

We realise that we are at, or past, the point of no return. We will not be able to paddle back up the creek against this current. We are now committed to seeing this through.

On the far side of the island or neck of land is another part of Willow Creek.

We leave the canal stretch and head into a twisty warren of tributaries.

Around this time we passed what looked like an inlet, but was a fork, an exit of water from the creek heading backwards from our general direction.

At this time I think we made the turn north in the angle of the "L".

We were encouraged by the trees, thinking of our intermediate goal to reach the glade in Minesing Swamp - Edenvale

Another marker at a fork in the creek. We follow the pointed direction.

The breeze has picked up, but the current is still strong. We start seeing small waves on the surface of the creek as the wind pushes against the current.

We are still doing OK. We like the trees that keep us company and long for the sheltered glade.

Here's another view

We start into a different format of the swamp; later we were to realise that we were in a huge lake, not our concept of a swamp.

Note that the reeds grow from the lake bed, perhaps four feet down; we are not looking at grass that is growing on a solid bank of earth. There is no solid ground here.

Those trees are standing in water.

Here is another, closer view of a reed bed.

The wind has strengthened, but under water the reeds show the flow of the creek.

We follow the flow of the creek, and relied heavily on the direction indicated by underwater weed growth.

We are now well into the increasingly-scary northward arm. The trees stay tantalisingly out of reach. They are only two minutes paddle away in a straight line, but the creek does not touch the trees, and we doubt we could paddle through the reeds; we certainly could not walk or swim through there.

And if we did reach the trees, we are still a very long and wet slog away from any road.

The wind is strong and bitterly cold. Much later, almost too late, I realised I should have been wearing my jacket, but when we set off the air was mild, the sun warm, so who needed a jacket?

The reed-bed streteches away for miles.

Here is a close-up; there is no above-water soil foundation for this growth, just a densely matted mess of dead reed leaves.

The dead trees were growing through the reed bed. The reeds continue behind that nearest dead tree. There is no land, just reed-clogged water.

The strong wind has bent over the reed-tops here.

Fred is smart; he is wearing a jacket. I am stupid, I have a thin green shirt over a thin cotton T-shirt. The cold wind is blowing through my clothes to my body, and blowing away my body-heat.

Look at the strength of the wind across the reed-bed. Look at the impact on the creek surface.

Fred spots a building. We agree that if we were to capsize here, we'd have little hope of reaching the building.

Miles of reed-bed surround us. Truly we are in the middle of a large lake, whose surface supports reeds.

The water is choppy.

On this little leg we are heading directly into the wind; this stretch of water is but a hundred yards long, yet, look at the size of the ripples, and some waves forming.

More chop.

The trees appeared quite suddenly; we thought we were done, headed into the glade, but no!

We found ourselves confused by the various arms of channels that opened away from us.

Dead ahead is another body of water; we are sure that is where we must end up, but should we go to the right or to the left?

Another quandry just nine minutes later.

We had many instances of this, where our way was not clear.

We knew we had to bear north, but the immediate means of doing that was not always clear.

We feared a wrong turn that would require is to paddle back upstream a ways against a current.

Here the swamp is truly flooded. The creek channel has disappeared; there is no sign of a flow of water, for it has spread over flat lands.

Now we seem to be in our glade, but has the water risen so high that we will not be able to pull in and stretch our legs?

We have been paddling for three hours non-stop, the last two hours strenuously against a strong head wind.

Just as suddenly the creek bed re-appears. We now seem to be paddling between two banks of a creek, than paddling in a gap in a vast reed sea.

Looking good, but still no land on which we could walk.

And suddenly again, we are in the glade.

Quickly we land and grab our lunch, sretch our legs.

Our bank is small, but the far bank is solid ground. We could walk out of here!

Here's a candid view of Big Red and some of Fred's sandwich.

The tree canopy is glorious.

Masses of ferns, three or four feet high, line the banks. Fred suggests we harvest them and take them back to the city.

The nest day I saw for $9.99 in Loblaws four-inch tubs with eight-inch ferns. Ten Dollars each!

We meet the two fellows at the blockage, and headed into the Nottawasaga River. The rest of the trip is plain paddling.

The current is strong, but so is the wind. At least we are not in peril on a lake!

The ususal luxurious tree growth meets us mid-stream.

More lush banks.

Five hours after we put in, we pull the canoe out. Fred is unpacking while I get Betty's car from the Edenvale Conservation Area car park.

Big Red meets Little Red.

Big Red meets Little Red.

By 16:00 we had driven back to George Johnson lane, transferred the canoe to Fred's car, and were headed south to our separate homes.

Ninety minutes later, in Betty’s condominium, I was still shivering – after 90 minutes in a heated car!